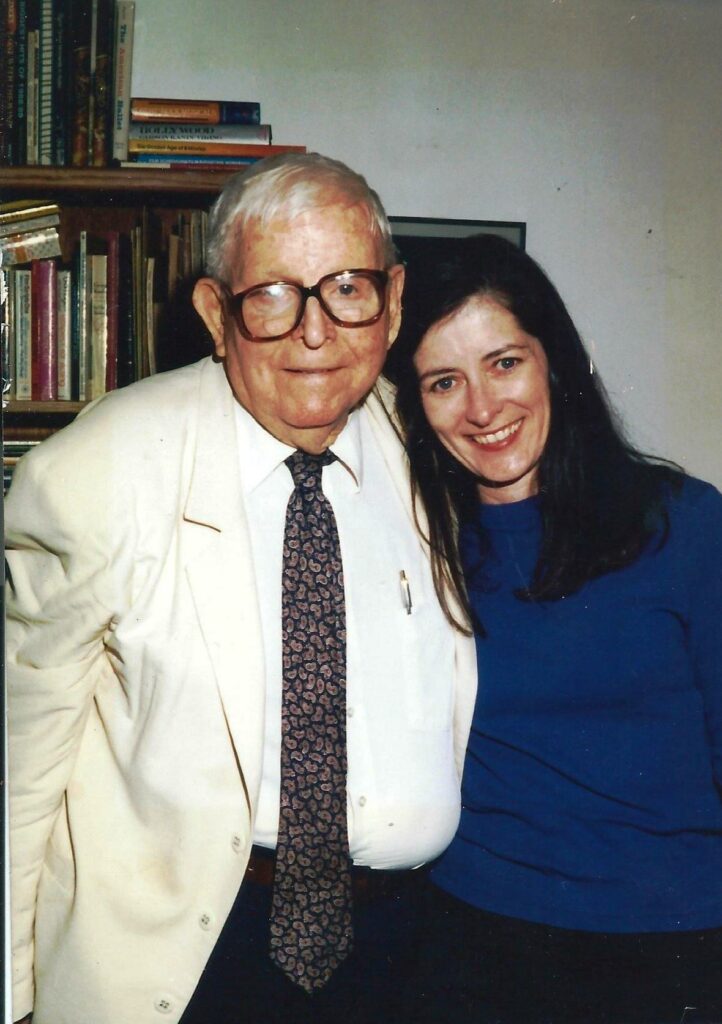

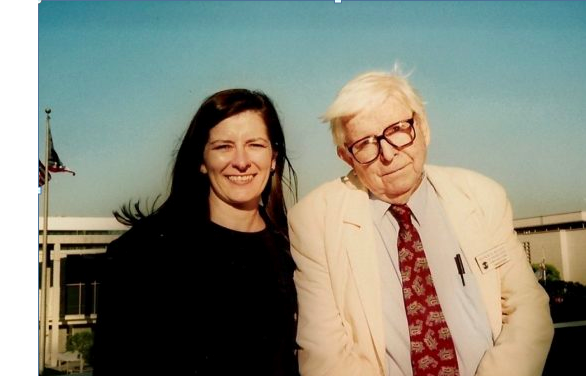

I knew Morris Kight personally for the last ten years of his life. I helped to prepare and fax many of his missives and correspondence. It was a time when I needed a job and he offered me part-time work. Morris was like that.

I became familiar with the 6:00 AM phone calls that many people who I interviewed also experienced. It went like this: the phone would ring at 6:00 AM and a chipper Morris Kight would be on the other end of the line. No hello, hardly a courtesy when he’d begin narrating the day’s agenda, all of which would be news to me. He would begin by making a statement about something that needed to happen that day, under his direction, as “a priority.”

Perhaps, it went something like: “We must be at city hall for the city council meeting that begins at 10AM when they’ll be voting on hospice funding. We must encourage the council to pass this important bill.”

He’d give me just enough time to agree or disagree to join his magic carpet ride for the day. And then just as quickly, the phone line would die. Without a good bye or a thank you or sorry to wake you, he hung up and busily went down a list, written on a yellow legal pad no doubt. At his memorial service in 2003, Ivy Bottini rhetorically asked the crowd, “Did Morris ever say goodbye before hanging up the phone?”

Many people thought they knew Morris. He was a bit of an enigma in that Morris was a loner who believed in the power of community.

For decades, Kight had devotees. Yet, his insecurities could suddenly slap his most loyal supporters in the face. The gratitude that I felt from most people went deeper than Morris’ political activism. It was personal, spiritual and life affirming. Some people I spoke with simply needed to vent. Others gushed. A few people refused to speak to me at all. His self-importance was legendary even without this biography. Yet some of his worst and most appalling qualities served a broader purpose that benefited many people.

It would take a huge, unstoppable ego to correct the deeply embedded imbalances and steadfast beliefs that made the world so hostile for homosexuals. As it turned out, it required many strong egos. The post-Stonewall gay movement tipped the equilibrium of society like no other civil rights movement had or has; it rocked the status quo from the inside out and the world, in my opinion, is a far more interesting and better place as a result.

One example is the Los Angeles Times refused to print the words “gay” or “homosexual,” much less cover the community with any amount of dignity and affirmation. They wouldn’t even accept a paid advertisement with those words. Morris Kight helped to change that and thus it opened discussions across America about the life of homosexuals. It was a long way from liberation, but it paved the road.

Some will ask was he magical or manipulative? In return, I must ask, does it really matter when looking at his impact on social reform?

Several people whom I spoke wanted to know why I was the one telling the Morris Kight story. It is a fair question. I sensed that Morris had a story that was worth mining. As I delved more deeply into Kight’s narrative, it became somewhat uncomfortably clear that this story is well-served by the fact that I do not have a personal claim in gay history. I have no stake in purifying it or prettying it up. I have enormous respect for the value of gay studies in world—and specifically American—history. My only agenda here is to tell the truth as kindly as possible. Yet the truth is not always kind. Because of the complexities and conflicts that Kight represents for some people, the scar tissue that surrounds his reputation, the utter dislike others have for his “ilk,” it became apparent that if I did not tell this story as honestly as possible with an objective perspective, probably no one else would.

Kight’s contributions could easily have been marginalized from the bigger account of gay history, which already continues to be at risk of its own marginalization.

No matter how unlikely it is that an effective gay movement could have been born from an upper middle-class, law-abiding, conservative populace, there are those who do not want gay history to be overly-identified with a liberal ideology. There are obtuse efforts to deny the “hippie” element that makes up a huge part of the DNA of gay rights. With the emergence of “Rainbow Capitalism,” many forget that the gay rights movement began as a social services outreach necessitated by families rejecting their gay youngsters. Gay and lesbian young adults were often disempowered and forced to lead marginalized lives, not fulfilling their personal potentials. It was not possible to argue for the rights of gays to marry when it was not legal for gays to walk down the street holding hands. Kight paved the way, one social policy at a time, to make it possible for gays to lead respectable lives of personal fulfillment and prosperity.

Morris wasn’t a weekend liberal. He didn’t facilitate a grass-roots movement once or twice in his life. He didn’t just show up at demonstrations with a sign. No, Morris was a life-long activist dedicated to a bigger, grander cause in the name of a better world for all. In the anti-war movement in the 60s, Kight co-founded the Dow Action Committee, the first successful corporate boycott in America, which effectively ended the manufacturing of napalm for use in Vietnam.

Post-Stonewall, Kight became a dignitary of gay liberation. In some circles, he was known as an egotist. Meanwhile, right down the street is another group of people who will describe him as a Gandhi-like godfather. And that is what fascinated me about him.

I discovered that Morris’ story fell naturally into the space where academic research meets old time chin-wagging. Areas of this story will remain open to interpretation and subject to perception. This book does not provide all the answers on the history of gay liberation; however, it may pose a few new questions.

We want our heroes to be faultless and altruistic—especially the ones who espouse the teachings of Gandhi. Gandhi himself, on his best day, was full of hidden human flaws. Kight, on the other hand, his flaws hung out like a stained shirttail at a Sunday social.

With his steadfast commitment to non-violent social change, he tarnished his do-gooder image with endless self-promotion. Despite all the successes along the way, accolades and awards, and the aspects of his work that will live on forever, Kight never believed that he received enough recognition.

It was a privilege to be of service to Morris. It has been an even bigger honor to tell his story. Kight’s story is about many people. His work ultimately affected the entire world in a positive way because it empowered individuals, homosexuals and all the rest of us, to make the world a better place.

Morris used to say that, “When I die, I’ll be dead. No need to go on about me being in a better place and all that stuff. I’ll be dead as dead can be.”

And so that is the way it is. Morris Kight is dead.

And yet, wherever a young gay man walks down the street holding his boyfriend’s hand, Morris Kight lives.

– Mary Ann Cherry

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on your website.